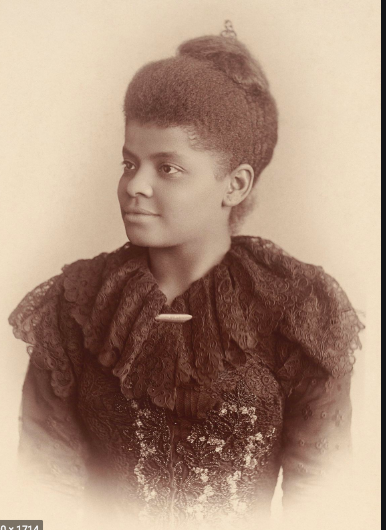

In his book The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness historian Paul Gilroy developed the theory of a culture comprised of African, American, Caribbean and British influences blended with European Enlightenment ideals. His metaphor for this cross cultural exchange of ideas between black-diaspora populations in The British Isles, the Caribbean, The Americas and Africa is the steam ship because that is how far flung activists in these regions were able to connect and communicate. Gilroy identifies one of these activists as Ida Wells, the crusading anti-lynching journalist who gained international attention due to two trips she made to The British Isles in 1893 and 1894. To the roll of names of activists who traveled and corresponded with each other across The Atlantic and around the world, must be added Catherine Impey, a white Victorian Quaker woman who lived on a farm in Street, Somerset England.

Catherine Impey was born into a family of abolitionists who had become active in the Temperance movement after the abolition of slavery had been achieved in Great Britain and The United States. Catherine was an enthusiastic member of The Independent Order of Good Templars (I.O.G.T.), an organization with rituals and social activities similar to The Freemasons but devoted to Temperance. Catherine’s participation on The I.O.G.T. allowed her to take part in meetings, travel throughout the British Isles and to the United States and engage in animated activism and discussion on her two most valued principles: Temperance and anti-racism.

According to Caroline Bressy’s book Empire, Race and Anti-Caste (Bloomsbury, 2013) Askew House,The Impey’s home in Somerset was visited by talented people of African-descent who had maintained ties after the abolition of slavery had been achieved. The poet Paul Laurence Dunbar and feminist teacher Fanny Jackson Coppin visited Askew House during the 1870’s. Ida Wells signed the guest book in 1893 leaving the following notation:

For whatever men say in blindness

and in spite of the fancies of youth

there’s nothing so kingly as kindness

there’s nothing so royal as truth. (Bressy, 8).

Quakerism was the guiding principle of Catherine Impey’s life. Quakers believe that all humans contain an inner light. By realizing the inner light inherent in all people, universal brotherhood may be achieved. The Quakers were a small minority in England by the 19th century but they were politically active in liberal politics, Temperance, and anti-racism. For Catherine Impey, a young single woman in her twenties, Temperance work allowed her to gather with like minded people not just in England but in The United States as well. Temperance activism allowed Catherine to branch out socially and to develop her intellect. Catherine journeyed across the Atlantic to America to take part in Temperance meetings. On these trips Catherine had the opportunity to engage in discussions about society and religion with talented journalists, poets, religious leaders and philosophers, many of whom were of African descent.

Catherine was heartbroken when her beloved organization was divided by controversy over segregation. In 1878 A Good Templar lodge in Kentucky asked to join The I.O.G.T. as a segregated lodge. The Good Templars in Kentucky insisted that there was no way they could accommodate negro members. The controversy raged in England, where I.O.G.T. meeting houses were integrated. The I.O.G.T. of England boasted 200,000 members. When the I.O.G.T. decided to allow segregation, The British I.O.G.T. broke away to form the Right Worthy Grand Lodge (R.W.G.L) which vowed to promote integrated Temperance lodges. Catherine felt pained by the negative influence American racism exerted upon her beloved organization.

In 1878 The. R.W.G.L. appointed Catherine Impey Secretary to the Negro Mission for The United States. In this capacity she traveled to Boston, Massachusetts for the R.W.G.L.’s International Conference at Pythian Hall. Catherine stayed at the home of William Wells Brown, an African-American author who hosted many of the renowned African-American attendees to the R.W.G.L. conference. Catherine observed that upon her first visit to America, she had “established a large circle of colored friends almost before she had any extended knowledge of white Americans.” (Bressy, 33).

When the I.O.G.T. and the R.W.G.L. agreed to unify under the banner of segregation in 1886, Catherine was devastated. She had met too many amazing talented men and women of color during her years of Temperance advocacy. She believed that the Independent Order of Good Templars had initially been founded on the belief that Temperance and Universal Brotherhood went hand in hand. She resolved to start a new organization called Anti-Caste, where writers of diverse racial backgrounds could have a forum to write about their experiences and concerns. During the late 19th Century, segregation would become the law of the land in many U.S. states. Scientific racism was embraced by thinkers on the right and left throughout the western world and Imperialism and Colonialism were practiced by the most powerful European nations. Catherine and her collaborators would be fighting an uphill battle.

Catherine traveled to Saratoga Springs, New York to take part in the conference that would determine the merger of the I.O.G.T.and the R.W.G.L. Her criticism of segregated churches in the United States was taken as a condemnation of The Christian Church. Catherine had been raising the issue of racism in the Temperance Movement for a decade but her fellow Temperance advocates accused her of putting the politics of anti-racism ahead of the organizations’ primary goal of Temperance. Catherine’s vote of dissent against the merger was the only vote opposing the merger of the I.O.G.T and the R.W.G.L. Lodges. Upon her return to England Catherine resigned from R.W.G.L. in order to form an organization that would combat racism. This was how Anti-Caste was born.

Innovations in printing in England made pamphleteers the social media influencers of their day. Pamphlets could be created with words and photographs and drawings which could be used to grab the reader’s attention. Catherine asked Frederic Douglass to come to England to speak about the plight of African-Americans in the United States. Due to her travels in The United States, Catherine knew that the descendants of the slaves were being disenfranchised in the south and that black people throughout the United States were being segregated, mistreated and ostracized. Douglass said he was too old for a transatlantic journey but recommended Ida Wells, the young investigative journalist whose work on the real reasons behind the lynching of blacks in the south had recently made her a permanent refugee from her home in Memphis, Tennessee.

Although rape was always cited as the cause for lynching, Wells’s research demonstrated that men and women of different races often had consensual affairs which were then called rape by disapproving authorities. Wells reported that African-American men and women in the south were being lynched for trying to exercise their basic civil rights: voting, using the sidewalk or speaking out against injustice. Catherine Impey traveled to the United States in 1892 and met with Ida Wells in Philadelphia. For Wells, the meeting was cathartic.

It seemed like an open door in a stone wall. For nearly a year I had been in the North, hoping to spread the truth and get moral support for my demand that those accused of crimes be given a fair trial and punished by law instead of by a mob. Only in one city-Boston-had I been given even a meager hearing, and the press was dumb. I refer of course to the white press, since it was the medium through which I hoped to reach the white people of the country, who alone could mold public sentiment. ( Crusade for Justice, 86)

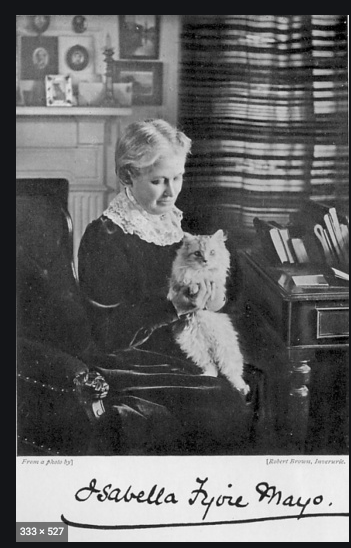

Catherine Impey’s goal of having an African-American speaker visit England was brought to fruition after a wealthy Scottish benefactor named Isabella Mayo joined Anti-Caste. Mayo was an author who had inherited a sum of money from her husband which she used to finance liberal causes. Ida Wells traveled to England aboard a steamship, suffering from seasickness throughout the ten day crossing from New York to Liverpool. Catherine brought Ida home to Somerset to recover for a few days. Wells had never been treated kindly by white people before. According to her memoirs, Ida appreciated the Impey’s hospitality but found the vegetarianism practiced by Catherine and many of her colleagues to be cult- like.

After speaking on the problem of lynching in the United States in England, Catherine and Ida traveled to Isabella Mayo’s home in Aberdeen Scotland to work on the latest issue of Anti-Caste. Mayo had turned her home into a boarding house for East Indians. Mayo’s confidante Dr.George Ferdinands, a young Sri Lankan Dentist who was of mixed Indian and English descent helped Wells and Impey with the production of a special pamphlet on lynching in the United States.

Catherine Impey returned to Somerset. Isabella Mayo brought Ida Wells to cities in Scotland and then to Liverpool and Manchester England to address audiences about the crisis of lynching in the United States. During her time in The British Isles, Wells was able to speak to over a thousand people to bring attention to the atrocities being committed against African-Americans.

While Ida Wells was making an impression on British audiences, Catherine Impey made a fateful decision from her home in Street, Somerset England. While working at Mayo’s house in close association with Dr.George Ferdinands, Catherine had felt a strong attraction to the young doctor, who was half her age. When she returned home Catherine convinced herself that Ferdinands felt the same way. Catherine wrote a love letter proposing marriage. Realizing her mistake, Catherine penned a second later apologizing to Dr. Ferdinands for her first letter and begging him to tear it up. Ferdinands, apparently feeling threatened by Impey’s love letter brought it to Isabella Mayo.

Isabella Mayo was a sincere activist who communicated with such leading liberal thinkers as Gandhi and Tolstoy. But she was not enlightened when it came to Western attitudes towards women’s’ sexuality. When Catherine traveled to Aberdeen to speak with Mayo about her love letter, Mayo was at first restrained. Ida Wells observed that over the next few days Mayo became increasingly hostile to Impey. Ultimately, Mayo confronted Impey in front of Wells. Mayo told Catherine that she was a “nymphomaniac” and must disassociate herself from Anti-Caste. She then told Wells that she must join her in disavowing Impey’s behavior. Ida Wells states in her autobiography that Mayo’s treatment of Impey was the cruelest interaction she had ever witnessed. Considering the fact that Wells was driven out of Tennessee by a lynch mob, and had once been thrown off a train by angry whites, her observation is telling of the intense hostility Isabella Mayo now bore towards the founder of Anti-Caste.

I had never heard one woman talk to another as she did, nor the scorn and withering sarcasm with which she characterized her. Poor Miss Impey was no match for her even if she had not been in the wrong. I really think it was the most painful scene in which I ever took part. I had spent such a happy two weeks in the society of two of the best representatives of the white race in an atmosphere of equality, culture, refinement, and devotion to the cause of the oppressed darker races. To see my two ideals of noble womanhood divided in this way was heartrending. When it was demanded that I choose between them it was indeed a staggering blow. (Crusade for Justice, 104).

Ida Wells refused to disavow Catherine Impey. She recognized that what had happened to Impey with regard to her feelings about Dr. Ferdinands was a natural thing that happened to people. Wells was controversial in the United States because she maintained that blacks and whites had consensual relationships that were then classified as rapes when white authorities felt the need to control black people. To Ida, the incident between Impey and Ferdiands was no different than incidents she had observed in Memphis. Ida’s own father was the product of a relationship between his white master and a slave, which made Ida herself a mulatto, which is how she was identified on the ship manifest for the ship that brought her to Liverpool. Ida had never heard the word nymphomaniac before she heard Isabella Mayo use it against Catherine Impey. Ida never spoke to Isabella Mayo again. She and her friend Catherine Impey made a visit to the son of the great British Abolitionist William Wilberforce in Liverpool before Ida had to leave to board her ship for the journey back to the United States.

The crisis between Catherine Impey and Isabella Mayo was devastating for anti-caste. Mayo used her power of the purse to ostracize Catherine Impey from her own creation, insisting that Anti-Caste and Ida Wells speaking tour would lose their funding unless Catherine left the organization. Catherine was later forced to make a humiliating public apology for her behavior in front of her fellow Quakers. Others in the Anti-Caste organization and anti-lynching crusade in England were forced to cut ties with Catherine. Because Ida Wells would not renounce Catherine Impey, Isabella Mayo cut Wells off and refused to pay for her ticket home. Mayo also wrote disparaging letters to Frederick Douglass and other prominent African-Americans in the United States decrying Wells support for Impey. To her credit, Wells stuck by Impey, ultimately proving to Douglass that Mayo was overreacting. Douglass, whose second wife was white and a good deal younger than he, was aware how controversial interracial unions between men and women of any age, let alone vastly different ages, could be.

Ida Wells made a triumphant return to The British Isles in 1894. She steered clear of Isabella Mayo and was saddened that the Quakers seemed to distance themselves from her. Ida regretted that Catherine and her friends did not know she had stood by her when Mayo was on the attack. The relationship between George Ferdinands and Isabella Mayo was also unique. According to The Scottish Index of Female Authors, Ferdinands was “like a son to Isabella Mayo and remained by her side for the rest of her life.” For Ida Wells, her sojourns to the British Isles were important because they taught her not to hate white people. For the first time, Ida Wells, who had been driven from her home by a lynch mob, learned that there were white people who knew that white superiority was evil and they were willing to work with her to help her and those being victimized by it.

Catherine Impey died in Street, Somerset England in 1924. Her obituary stated that her religion was her life. For Catherine, this meant working to help humanity find its inner light. Certainly, she was ahead of her time. A woman tripped up by an earthly passion for another person as she struggled to achieve her spiritual passion of civil rights for all. In this way she is reminiscent of Bayard Rustin another Quaker civil right activist, the pacifist advocate of non-violence whose homosexuality always forced him to work in the shadows of the non-violent civil rights movement of the 1960’s. Rustin is the man most responsible for the success of the 1963 March on Washington. Catherine would have enjoyed Dr.King’s I have a Dream Speech because it was about how transformative universal brotherhood could be. That was what Catherine Impey had dreamed of when she started Anti-Caste 75 years earlier.