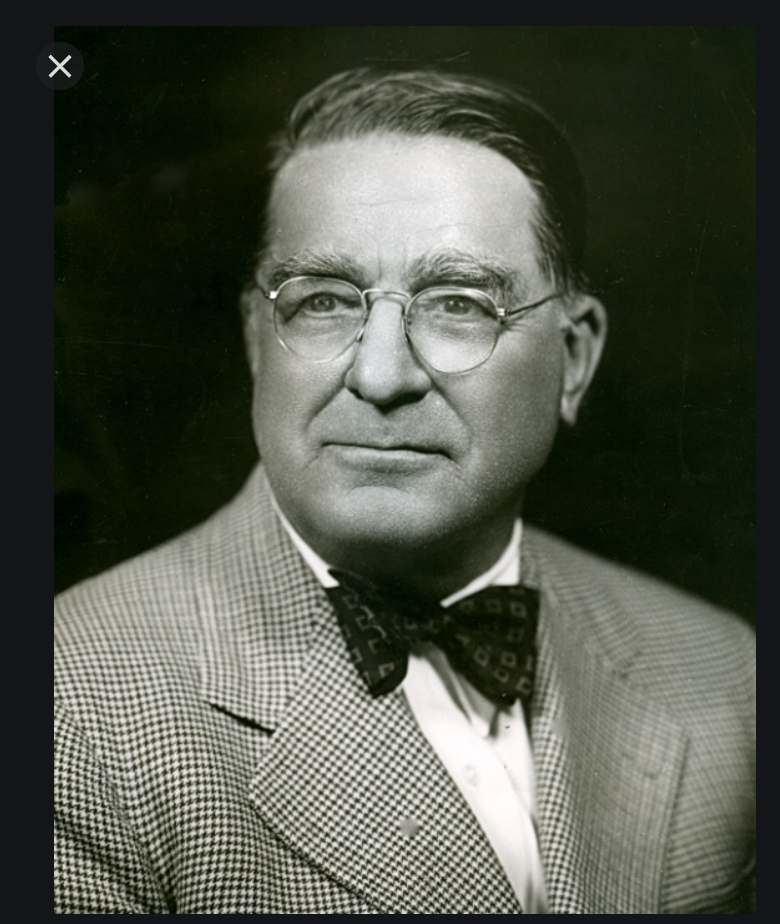

Kernan’s Road to Certainty

Overview: William C.Kernan was an outspoken anti-Fascist during the late 1930’s and early 40’s, as well as an advocate for social justice. During the late 1940’s and early 50’s he became a fervent anti-Communist, eventually becoming the spokesman for The Committee of 10. This committee tried to purge Scarsdale’s public school system of any and all materials that were believed to have any relationship to Communist ideas.

For William C. Kernan “the bomb fell” in January 1938. This is when he began a life of political activism aimed at preserving American Democracy. Kernan was the Rector of Trinity Episcopal Church in Bayonne, New Jersey. He had been alerted to the fact that Mayor of Jersey City Frank Hague, the political boss of Hudson County, New Jersey had refused to allow ACLU. founder Roger N. Baldwin give a speech on the grounds that Communists were involved. Kernan believed that the right to free speech must not be abridged. Despite the opposition of his vestry, he allowed Baldwin to speak at Trinity. The New York Times reported the story on January 15, 1938.

In Jersey City, anyone who spoke out against Frank Hague was considered a communist. Hague had stated as much to his Chamber of Commerce on January 12, 1938. “You hear about constitutional rights, free speech and the free press. Every time I hear these words I say to myself, ‘That man is a Red, that man is a Communist!’ You never hear a real American talk like that.” Kernan was certain that preventing Baldwin’s right to free speech was a violation of a sacred American civil right. He not only let Baldwin speak but cheered loudly throughout his speech. After the speech Kernan joined a group of young activists to form The Bayonne Council for Democracy. They appointed him President. According to his biography the Bayonne Council for Democracy held some private meetings and two public meetings, one that was broken up by organized hecklers.

Labor leaders were trying to run a socialist candidate against Mayor Hague. William C.Kernan had grown up poor. He had lost his first church after the stock market of crash of 1929. He believed that labor had a God given right to organize. He was happy to work with socialists because it was possible for them not to be associated with totalitarian governments like the ones in The Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, which had proven themselves to be godless regimes that turned their subjects into slaves of the state. Time Magazine 13 June 1938 reported that The Hague Administration in Jersey City had taken on aspects of “a fascist cell”.

Time cited the case of Kernan’s anti-Hague associate Rabbi Plotkin, who was evicted with his congregation from The Jewish Community Center in Jersey City because he had spoken out against Hague’s refusal to allow free speech. Other Jews in Jersey City had gone along with the eviction, stating that Plotkin was a Communist. If one used Frank Hague’s definition of a Communist, he was. Kernan worked hard to oppose Hague’s dictatorial rule in Hudson County but had little to show for it. He and his associates had no money and little political power. Those who had jobs or rented property in Hudson County knew that they or their family members had a lot to lose if they ever spoke out against Frank Hague.

For those who lived under Frank Hague’s rule things were not always so bad. Hague was a Catholic who was supported by Hudson County’s working class, most of whom were Catholics. In his 2011 biography of Frank Hague, author Leonard F. Vernon goes to great lengths to explain why he was popular with many of his constituents. Those Catholics who could recall their ancestors earlier experiences in Hudson County recalled years of Protestant oppression, when their faith was disrespected and they had no control over their own lives because Protestant politicians held the reigns of power. Frank Hague had provided safe neighborhoods for a generation. He had used tax revenues to build a municipal hospital that served Jersey City’s residents, often at no charge. Hague’s resistance to labor unions had allowed sweat shops to thrive in Jersey City, but there was work for those who needed it, no small feat during the Great Depression.

Ten months later an incident occurred at Trinity Church that provided Kernan with a clearer focus about how to direct his political activism. One of his parishioners was fixing a light in the church when Father Kernan saw him. The parishioner informed his pastor that thanks to the radio priest Father Coughlin he now knew “the truth about the Jews.” When Kernan asked him “what truth?,” the man responded that Coughlin’s radio broadcast had taught him that the Jews were Communists who started the revolution in Russia and “were responsible for bad conditions in Germany.”

At this precise moment Kernan found himself “burning with indignation.” He realized it was futile to preach the Gospel of love and justice if people like his parishioner could be convinced to hate Jews simply by listening to Father Coughlin on the radio. He realized that “millions of Americans were in a frame of mind to turn statements into the kind of propaganda that had been part of the enslavement tactic of the Nazis. Suppose it should happen here!” He told his parishioner to “get down on his knees before the altar and implore God’s mercy and forgiveness” because the fact that he had listened to and believed Father Coughlin “was a most serious threat to his soul’s salvation.”

Kernan traveled to New York City “to find out exactly what Coughlin had said and trace down his source material. I spent days in New York in pursuit of this purpose. I searched newspaper files, interviewed people in order to gather facts and to get leads that might produce more facts, read pertinent official documents in the British Library of Information and inquired into the religious and national backgrounds of the men who were responsible for the Bolshevik revolution in Russia.” Kernan then wrote an article titled “My Answer to Father Coughlin” which was published in The Nation as Coughlin, The Jews and Communism.

He and his friend Bob Ambry went to WEVD in an effort to obtain broadcat time to oppose Frank Hague’s dictatorial rule in Jersey City. WEVD had been started by socialists, its initials are those of the Socialist leader Eugene V.Debs. The station had no interest in Kernan and Ambry’s broadcast plans. As the two men were walking out of Producer George Field’s office, Ambry turned around, pulled Kernan’s Nation article out of his pocket and handed it to Field. “How about an anti-Coughlin broadcast” he said. Field was interested in that. WEVD, the radio station that had aired Father Coughlin’s anti-Semitic broadcast, agreed to have Father Kernan give his rebuttal to Coughlin’s accusations, after which Kernan became a regular speaker on WEVD’s Thursday night radio program. For the next decade, William C.Kernan would have a part time career as a radio speaker. As the United States remained on the fence with regard to participation in the war in Europe, Kernan would speak out against fascism and communism. But as the 1940’s progressed he also took part in the program Meet the Critics, often giving “The Christian Point of View” on topics of the day or discussing the latest bestsellers with other critics.

Father Coughlin would no longer be broadcast on WEVD because he refused to submit a text of his speech 48 hours prior to speaking. In effect, the Reverend Kernan had replaced Father Coughlin. He would speak for justice and human rights and against totalitarianism. He would also speak against The Christian Front, an organization that had formed to protest the fact that Father Coughlin had been banned from WEVD. The Christian Front advocated The Christian Index, a pledge not to do business with, buy from or hire non-Christians. Kernan realized that was the same type of boycott that had removed Jews from participating in public life in Germany. The Reverend Kernan made it his cause to oppose “Commu-Nazism,” which he defined as propagandists who misused the right to free speech and assembly to advocate Communist or Nazi ideas in an effort to bring totalitarianism to the United States.

For the next two years this would mean primarily opposing organizations like The Christian Front and The German-American Bund, which advocated fascist ideals while cloaking them with American or Christian icons or sacred words. For example, The Christian Front distributed a pamphlet stating that Jesus Christ supported The Christian Index. As an Episcopal priest, the Reverend Kernan was deeply disturbed by this misuse of Christianity. He felt it was his sacred duty to oppose those who were taking advantage of America’s freedoms and libeling Christianity.

The vestry at Trinity Church in Bayonne was opposed to the Reverend Kernan’s political activism. He resigned as Rector during the month of December 1939. The Bayonne Council for Democracy disbanded as well. The young man and woman who had urged Kernan to form the council and become its president informed him that they were proud Communists. Kernan briefly notes this fact in his biography.

Stalin and Hitler had recently signed the German-Soviet Non-Aggression pact, giving Father Kernan further proof that both Communists and Nazis were cut from the same totalitarian cloth. Then they had attacked Poland and precipitated World War II in Europe. The United States remained neutral but President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s government arranged to support Great Britain. This was controversial: the battle for the hearts and minds of Americans had begun.

Although there was little money in it, Reverend Kernan vowed to keep up his public battle against Commu-Nazism and for social justice in The United States. He and his wife Jean had three children and another on the way. In his autobiography Kernan recalls: “I had no job and could count immediately on no regular income from any source. But we never lived our lives together with security as the main objective. We were trying to do the will of God as he gave us light to see it, and when principle came into conflict with security, we chose principle even if it meant the temporary sacrifice of security.” He had been advocating for The United States to take a strong stand against totalitarian aggression abroad while at the same time fearing totalitarian subversion on the homefront. He had come to believe that a “Fifth Column” was active in The United States and that the people in charge of it wanted to bring about totalitarian rule in The United States. He no longer believed that free speech should be protected in all cases.A 24 June 1940 New York Times article reported that Kernan had urged the outlawing of 5th column elements comprised of Nazis, fascists and communists in the United States. Kernan believed that agents of this 5th column misused the Bill of Rights in an effort to take over the nation from within.

Jean Kernan found a house for her family on Ferncliff Road in the prosperous suburb of Scarsdale, New York. Kernan would recall that the first few months in their new home “were marked by more hardship than we cared to admit to ourselves. There was no question of trying to keep up with the Joneses. We could not even keep up with the milkman. He was a nice person, but once we owed him so much money that I dreaded the sight of him.” Kernan and his wife were “painfully conscious” of the contrast between themselves and their wealthy neighbors. They were put more at ease by the fact that although they were the only Roosevelt Democrats in the area, their neighbors “were good and friendly” and all of them helped to look when three year old Peter Kernan wandered off; not giving up their search until he was brought home by the police.

The Episcopal Church of St. James the Less was one place in Scarsdale where the Reverend Kernan felt at home. He was a “high churchman” which meant that he believed that The Episcopal Church was one branch of The Universal Catholic Church that had been founded by The Apostles. Like The Eastern Orthodox Church, The Episcopal Church had broken with The Roman Catholic Church but maintained many of its sacraments. Not all Episcopalians believed in High Church principles. This lack of certainty bothered Kernan. One thing that immediately appealed to him about St.James the Less was that its rector James Harry Price had once given an address in which he had stated that “some things in life never change, such as the existence of God, the Ten Commandments and the multiplication table and that from these we may draw certainty in a world rapidly drifting into confusion and chaos.”

Father Price asked Father Kernan to be his part time assistant minister. Kernan was happy to find a kindred spirit as well as a paying job. “We were both worried about the lack of certainty regarding the nature of Truth which we encountered everywhere.” Kernan relates in his autobiography that Price eventually convinced him that there were “absolutely devastating effects on man’s life once the conclusion is reached that there is no Truth-can be no Truth-because, as so many affirm, all Truth is relative.”

Father Kernan arranged to work for three days at St. James the Less as assistant minister and to spend the other four days of the week in Manhattan. In New York City and elsewhere he would work for three things: support for President Roosevelt and the need for the government and people of The United States to aid the allies against Germany, opposition to “shifting attacks upon American Democracy” by Commu-Nazi organizations in the United States, and social justice for all Americans regardless of race, creed or color. He had a weekly radio show on WEVD and was given an office there to answer the voluminous amount of mail his speeches generated. Some of the mail contained hateful attacks by racists and anti-Semites.

To encourage American involvement in the war in Europe he joined The Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies. This group opposed America First, an organization led by Charles Lindbergh that wanted to prevent American involvement in the war. Kernan did not believe America First misused free speech. Although he was opposed to the organization’s goal he recognized that it was comprised of Americans using their right to free speech, as he stated in a letter to The New York Times. He spent a lot of time at Freedom House, an organization dedicated to promoting American Democracy at home and abroad. He would eventually be appointed to its board of directors. To fight for social justice for the poor, organized labor and minorities he became a founding member of The Liberal Party, a new organization created by the right wing of The New York State American Labor Party because they believed that people “in the communist camp” controlled the labor party.

During his three days a week at St. James the Less, Kernan found himself in agreement with Father Price’s emphasis on education. Price was an outspoken critic of modern education. On April 29, 1940 The New York Times reported that Price stated in a sermon at The Cathedral of St. John the Divine “Modern education is not necessarily irreligious or anti-religious, it is just that it is secular and worldly and little attention and consideration are paid to the fundamental truths about life and living-the things that make Western Civilization great.” Price was upset by the fact that “very modern parents” don’t allow their children to receive religious instruction “until they are old enough to decide for themselves.” Price believed that religious instruction should be like academic instruction or personal hygiene, something that parents started their children on at an early age. On September 20, 1943 The New York Times reported that he had founded Education for Freedom, an organization that would use famous educators and other well-known people to warn Americans of the crisis in Education and the need to raise educational standards. This information would be provided in a series of radio broadcasts by Red Barber, Walter Lippman and others.

Kernan joined Price in applying their educational ideas to their religious instruction at St.James the Less. They believed that “Education ought to liberate man from the tyranny of appetite, and that required discipline-and you could not have discipline without Truth from which come standards in the light of which, discipline was undertaken.” The two priests sought to teach the young people at St.James the Less to “learn to subject their instincts and passions to the control of reason and will.” One of their students was Nancy Moore. She felt that Father Price and Father Kernan truly challenged their pupils in an engaging, respectful manner.

These are her recollections from an email dated December 7, 2012:

“Very important to us were two occasions during the year: one was the Christmas pageant, which was directed by a parishioner and the music director, and the other was a Passion Play which we called the “Mime” because it was done in very slow pantomime. One of the clergy was at every rehearsal at the beginning, and began with a prayer. Instead of teenagers “hacking around” we turned into serious young people with the heavy responsibility of portraying the Stations of the Cross. One went from role to role as one grew older: from a Woman of Jerusalem to Mary Magdalene to Veronica to the Virgin Mary for the girls, or, if you were a boy, from a centurion to John or Simon of Cyrene or maybe Pontius Pilate — and maybe eventually to the central figure — the “Christus.”

Father Kernan’s handsome son Patrick played the Christus several times, as I remember. I remember the year my brother Bob was the Christus: it was so moving I had to go out to the cemetery to have a good cry! The special music played by the organ to accompany the movement had been arranged by Hugh Ross, who had been the organist at the time the tradition began, thanks to a parishioner who had gone to Paris to study mime with Marcel Marceau’s teacher, whose name I don’t remember for sure. (Etienne Descreux, I think.)

Anyway, this experience might have been the kind of educational approach that you have heard about, although I don’t know that for sure, either. I just know that actually going through the Passion story with my body was an example of learning as a whole person, not only with my intellect.

We also had the opportunity, as girls (who could not yet acolyte — that was still “boys only”) to join the Junior Altar Guild, which gave us a hands-on experience of preparing the altar for services and thus contributing with our work to the liturgy. I vividly remember the altar guild chairperson advising us to be as careful in our work with the linens and vessels to make everything as perfect as we would “if we were giving a dinner party” (a comparison that stuck with me, probably because my mother was more casual when she had company!) But, again, there is the example of our being taken seriously, which was the most important aspect of our Christian education!

But our intellects were engaged often and quite seriously. We had to learn the whole catechism in the back of the Prayer Book by heart, for example, to prepare for confirmation. It is fortunate that we did, because the bishop quizzed us about it (possibly at the instigation of the clergy!).

Nancy recalls a specific time that Father Kernan had her make an appointment to speak with him about a question she had. It was the first time in her life that she had an adult conversation. The experience made her feel intelligent and valued. The fact that Kernan believed Father Price’s views on education to be correct further convinced him that “We could consider objectively the disastrous effects of uncertainty and confusion in the world.” He was troubled that this same uncertainty plagued The Episcopal Church of St .James the Less.

Throughout the decade, parishioners often left the church because its form of worship was too high and Price and Kernan were too demanding with regard to their expectations,.such as the requirement that church members attend church every Sunday. Kernan noted that this problem had existed before he joined St.James the Less. He felt it was directly related to the fact that the elected parishioners who ran the church, the vestry, had too much power over the church’s clergy. In fact the vestry had the power to fire its clergy if so inclined.

Although The Kernan family had come to Scarsdale in 1940, it must have been easier for them to fit in during the war years. Rationing was a great equalizer. What the family could not afford did not matter as much with Word War II going on and most material good forsaken for the war effort. By the end of 1945 The Nazis and The Japanese had been defeated but for the rest of the decade it appeared that the Communists were winning the war for hearts and minds in Europe and Asia. Indignant over the fact that many of his liberal friends did not share his loathing of Communists or his belief that they could take control in The United States, Father Kernan had resigned from the Board of Directors of Freedom House. He no longer considered himself a liberal because the liberal movement “had become Godless.”

In 1949 A female parishioner at St.James the Less took him aside one January day to ask if he could look into the background of a prominent educator who had been chosen to speak before her chapter of The Daughters of The American Revolution. One of the members said the educator was a Communist. She asked Kernan to find out. Just as a bomb had dropped regarding Father Couglin and fascism in 1939, now a bomb was being dropped regarding communism in 1949.

Eleven years earlier, Kernan had researched Father Coughlin’s accusations that Jews were Communists and begun a decade long anti-Fascist, pro social justice crusade. Now he would again do research into accusations of Communism and reach a different conclusion. He was directed to Otto E. Dohrenwend, a New York businessman and Scarsdale resident who had become a self educated expert on Communist subversion after serving as a juror on a 1947 U.S. Federal Grand Jury investigating activities of Communists in the State Department. Dohrenwend provided Kernan with the names and backgrounds of several people who were associated with Communist fronts who had been allowed to address the Scarsdale PTA and the Scarsdale Teachers Association.

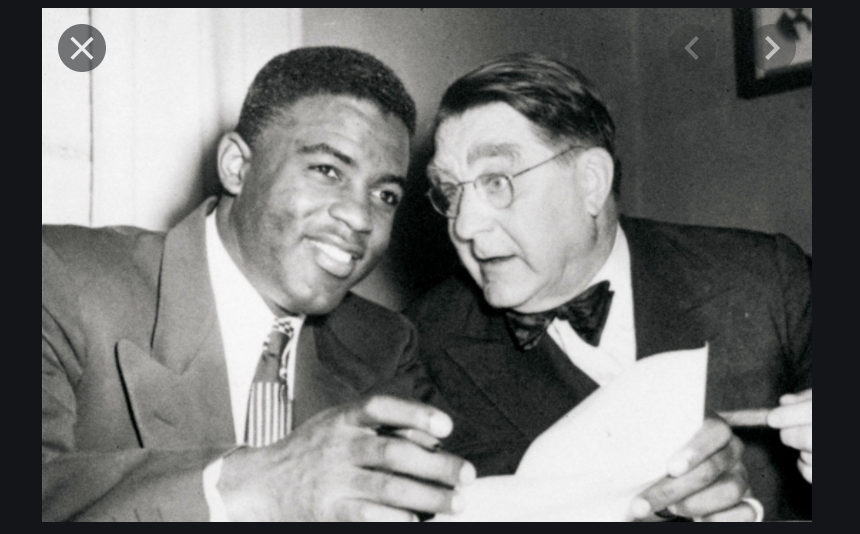

Dohrenwend related to Kernan the fact that Attorney General Clark had warned that Communists were trying to indoctrinate young children to their ideology. As proof that this had already occurred in Scarsdale, Dohrenwend pointed out that admitted Communist Howard Fast had eleven novels on the shelves of the Scarsdale High School Library. There was also a poetry anthology that contained work by Langston Hughes, whom the House Un-American Activities Committee had listed as being associated with 71 Communist front organizations.

Kernan had enough facts from Dohrenwend. He was dismayed to hear that Mr.Dohrenwend had already spoken to the head of the Education Committee at The Scarsdale Town Club, Scarsdale’s governing body, Vernon Smith the superintendent of Scarsdale Public Schools and A. Chauncey Newlin, president of The Board of Education.

Nothing was being done about what Kernan and Dohrenwend saw as an obvious case of Communist infiltration. In 1940, Father Kernan had written The Ghost of Royal Oak a book that outlined his opposition to fascism and communism. He referred to people who pushed the fascist or Communist agenda as propaganda termites because “Like termites which eat the stout timbers of a strong house until they have destroyed it, these Nazi and Communist agents, spies and sympathizers in America are undermining our democratic institutions, our churches our schools, our trade unions and our homes.”

The fascists had been defeated yet Communists were tolerated in liberal circles, especially if they had renounced any previous communist affiliations. Father Kernan believed that “both Communism and Nazism were palpably evil.” He had been traveling a majority of the time during the previous decade, promoting his social justice, anti-totalitarian agenda. Now that he was back in Scarsdale with Jean and their six children he had another battle to fight against Communist propaganda termites in the Scarsdale Public Schools. Kernan the socialist was about to become Kernan the red-baiter, a term that he did not find offensive. In fact, he had stated in his 1940 book The Ghost of Royal Oak that red-baiter was a sinful word created by Communists to prevent decent people from criticizing their methods.

Father Kernan and Otto E. Dohrenwend joined with eight other concerned citizens of Scarsdale to form The Committee of 10. The group was non-sectarian and non-denominational. The Committee sent communications to The Scarsdale Inquirer, periodically mailed newsletters to every resident of Scarsdale and held neighborhood meetings. The committee targeted the novels written by Howard Fast, who had joined the Communist Party in 1943. Father Kernan read excerpts from Fast’s novel Haym Salomon, Son of Liberty, a historical novel set during the Revolutionary War. He cited passages from the book that spoke negatively of war profiteers in Philadelphia, asserting that these passages were evidence that Fast was trying to incite class hatred.

The Board of Education disagreed with Kernan’s assertion that Fast’s novel was Communist propaganda. Fast could no longer find a publisher in the United States and the U.S. Government had revoked his passport because he refused to testify before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. He eventually published his novel Spartacus on his own and it went on to become a bestseller and a popular Stanley Kubrick film starring Kirk Douglas. (Spartacus was the Roman slave who led a rebellion against The Roman Republic. He and his followers were eventually captured and crucified along The Apian Way, 40 years before the birth of Jesus Christ.)

The Committee of 10 turned its attention to books by Paul Robeson and Langston Hughes. A Robeson biography was on a recommended reading list for eighth graders; it was removed from the list but remained on the library shelf. Books by Arthur Miller and W.E.B. Dubois were objectionable to The Committee of 10 as were others by various authors who had been blacklisted in other parts of the United States. Kernan and The Committee of 10 had certainty that they were defending democracy by demanding the removal of the books but they could not convince the Scarsdale Public School system to remove them. Superintendent Newlin stated that Scarsdale schools would continue to expose their students to a variety of points of view. Kernan and his fellow committee members were outraged.

The Committee of 10 began naming Communists and those who had participated in Communist fronts when they found out that they were speaking or appearing in Scarsdale Public School buildings. According to Kernan’s biography, the Committee of Ten attracted over 1,000 members and changed its name to The Scarsdale Citizens Committee. Throughout 1951, two professors and a dancer with Communist ties spoke to students or performed for students in the Scarsdale Public Schools. Father Kernan was especially galled that Dr.Bernard F.Reiss, Psychologist and Professor at Hunter College had been permitted to speak to 11th and 12th graders on career day. He pointed out that Reiss had signed a statement for The Daily Worker in 1943 that defended The Soviet Union’s hanging of two Jewish anti-Nazi labor leaders in Poland in 1941.

Father Kernan was greatly influenced by the book Men Without Faces by Louis F .Budenz. He had been a Communist Party member during the 1930’s but had rediscovered his Catholic faith in 1945 and become an important F.B.I. informant and the man Senator Joseph McCarthy would rely on for his Senate hearings investigating Communist activity in the United States government. Budenz maintained that Communists wanted to infiltrate the high society of Westchester County by having “concealed communists speak before community organizations as experts on foreign policy, pro communist books would be plugged at informal dinner parties, in women’s clubs, study groups and educational institutions” (italics mine). Kernan felt that he and The Committee of 10 had uncovered the Communist plot Budenz had written about a year before Men Without Faces was published.

The citizens of Scarsdale opposed to The Scarsdale Citizens Committee mobilized as well. Eighty-one prominent Scarsdale residents signed a petition condemning “book banning.” The Board of Education eventually refused to let members of the Scarsdale Citizens Committee speak at its meetings. New School Superintendent Archibald B.Shaw read a compassionate statement swearing to the loyalty of Scarsdale School Teachers at a special public hearing before the Board of Education on June 19, 1950.

Kernan felt this was manipulative because his committee had not specifically accused the teachers of disloyalty. In fact the Citizen’s Committee had stirred up such a negative atmosphere that one former student recalled “half of the Scarsdale High School faculty were accused.“ A popular history teacher named Dorothy Connor told her class “All my life I have tried to give my students a love for their country. And to be called a Communist is pretty hard to take.“ She then broke out in tears. Like the Reverend Kernan, Connor had been a Roosevelt Democrat and a New Deal Liberal.

The president of The Fox Meadow Elementary School PTA apologized for allowing the Communist dance instructor Pearl Primus to perform at Fox Meadow. She was not re-elected. The Scarsdale Women’s Club, the PTA’s. The League of Women Voters, and The Scarsdale Inquirer all came out against The Scarsdale Citizens Committee. The motto of the committee’s opponents was “Save Our Schools.” Again, Kernan was flabbergasted; he felt that he and his fellow members of The Scarsdale Citizens Committee were the ones trying to save the schools.

The Scarsdale Citizens Committee held a special meeting at Edgewood School on March 27, 1952. Father Kernan states in his autobiography that between 700-900 people attended. He, Otto E.Dohrenwend and the other speakers had prepared questions asked of them by sympathetic crowd members. Opponents criticized this as a fascist tactic but Kernan felt this was hypocritical because it was he and his supporters who had been silenced at Board of Education meetings. A. Chauncy Newlin wrote an open letter to The Scarsdale Inquirer the following day stating that if something were not done to silence the committee, people would lose good teachers and be unable to attract new teachers to the Scarsdale public school system.

The Board of Education was reelected and the furor subsided although Kernan maintained that he and his supporters continued to believe that their evidence showed the Communist influence in the Scarsdale Public School System. Scarsdale Town Historian Eric Rothschild, son of the Edgewood Elementary School librarian during the early fifties Amalie Rothschild, recalls that the last time Kernan was at the Board of Education meeting he stormed out of the building yelling “Is this America? Is this Democracy?” because he had not been allowed to speak.

Father Kernan had been having spiritual doubts while waging his anti-Communist crusade in Scarsdale. He found that he sincerely believed in several tenets taught by the Catholic Church, such as the immaculate conception of Mary, invocation of the saints and the sacrilege of birth control. These were not tenets of the Episcopal faith and he had to keep silent about them. The uncertainty of The Episcopal Church troubled him. “I sought Christ’s Truth which cannot change or mean something different to every man.” He could no longer accept that spiritual truth in The Episcopal Church was open to interpretation from parish to parish. Father Kernan wanted one universal truth that could provide him with certainty because it was “the Truth of Christ.” He had become good friends with fellow citizen’s committee members Mr. and Mrs. Robert Fitzpatrick. They introduced Kernan to Father Ferdinand Schonberg a Jesuit based in Philadelphia. Kernan began consultation with Father Schonberg about his crisis of faith. He realized he needed “real authority- as the power to require acceptance of the teachings of the Church by its members.” Schonberg gave Kernan books to study about Catholicism. He became convinced that The Episcopal Church was not part of The Catholic Church. “They can not have now what they rejected at The Reformation four hundred years ago.”

On Monday, May 5 the vestry of St .James the Less called Father Kernan in for an emergency meeting. He was informed that he had to give up his anti-Communist activities with the Scarsdale Citizens Committee or resign as assistant minister. The stated reason was that people were leaving the church and it was losing money. When Kernan said he could not give up his work with The Citizen’s Committee, the vestry consulted the Bishop who suggested a cooling off period.

Father Price refused to let Kernan go, and Kernan took a week to think about this situation. He decided that it was the answer to his prayers because he wanted to convert to Catholicism. He stated his beliefs and his intentions in a letter to Bishop of New York Horace Donegan. On May 21 he made his profession of faith at Immaculate Heart of Mary Church in Scarsdale and was baptized by Father Schoberg.

Kernan’s departure from St.James the Less and subsequent conversion to Catholicism caused quite a stir. It was reported in The New York Times and Time magazine. Bishop Donegan took exception to the departure for the Catholic Church when he gave a sermon installing a new rector George French Kempsell, Jr. in 1953. Father Price had left St.James the Less and converted to Catholicism a year after Kernan had. Donegan stated that the Episcopal Church was democratic because the Laity voted for their clergymen. Kernan responded at a Communion breakfast in New York City that “Bishop Donegan would be hard put to it did he try to prove that in founding his church, Christ gave power to the laity.”

William C.Kernan had found certainty in an institution that was based on the one totalitarian leader he could trust in, God. He became a lay worker for The Christopher’s, a Catholic aid organization. For the next ten years, he would travel to give speeches to Catholic groups about his experiences. Jean and all six of his children all converted to Catholicism. He always stated that The Catholic Church gave him moral certainty. On 14 May 1967 The New York Times reported that Kernan was Director of Training at Horn and Hardart. He had applied the educational methods he and Father Price had utilized twenty years earlier at St.James the Less Church in order to give 13 juvenile delinquents a chance to work in the cafeteria business. He told the reporter John M.Taylor “It’s unfair the way society pins a label on these kids. Sure they dropped out of school and got into trouble. But they’re fine youngsters and I’m proud of them. I just hope we can teach them to be proud of themselves.” The last written record of him appears in a letter to the editor of The Long Beach (California) Journal in 1973. He adamantly stated why an editorial sympathetic to abortion was wrong. He made his case with great certainty. He lived to be 92 years old.

Author’s Note: Material for this article has been gathered from The New York Times articles, which have been cited in the text. William C. Kernan also had three published “Letters to the Editor” of The New York Times that presented his views on the misuse of free speech by enemies of The United States, his opposition to the internment of the Japanese during World War II and his belief that there were certain truths (such as the belief in God and the correctness of The American Creed) that all Americans should agree upon. Text that appears in quotations are the words of William C. Kernan and have been quoted from his books The Ghost of Royal Oak (1940) and My Road to Certainty (1953). I have used information from ancestry.com to determine that William C. Kernan died in 1992 at the age of 92. Information about Frank Hague was drawn from Time Magazine articles and The Life and Times of Jersey City, Mayor Frank Hague “I Am The Law” by Leonard F.Vernon. Charleston: The History Press 2011.