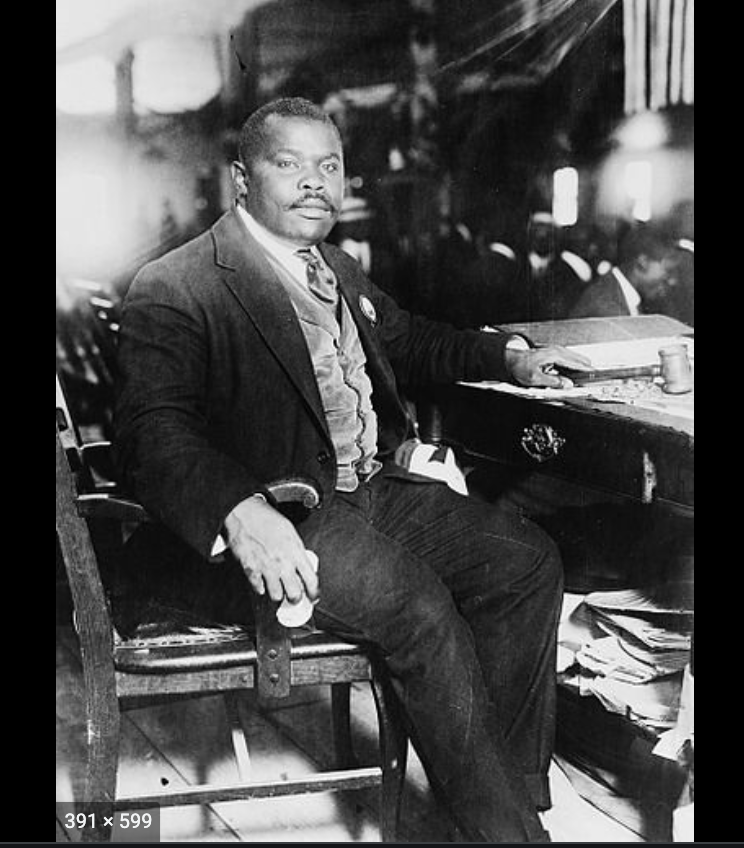

In 1914 Marcus Garvey created The United Negro Improvement Association (U.N.I.A.) in Kingston, Jamaica. His organization sought to improve the lives of black people through education, race pride and vocational endeavors. Garvey’s organization was unique because it identified itself as Negro at a time when upwordly mobile Jamaicans sought to identify themselves as anything other than black. While Garvey’s appeal to a large group of people whose ancestors had been slaves was comendable his love of pomp and circumstance and self aggrandizing gestures often supplanted the good works he and his organization promised.

Garvey left Jamaica for the United States in 1916. After a difficult year in Manhattan, He first traveled to Booker T.Washington’s Tuskegee Institute with the expectation that he could find support for his fledgling United Negro Improvement Association ( U.N.I.A). It was Booker T.Washington’s autobiography Up From Slavery that had first inspired Garvey to become a race leader. Garvey was impressed with Tuskegee and the model it provided for agricultural science. However he received only cursory meetings with the school’s administrators. More instructional were his visits to 38 mostly southern states where he witnessed the powerful influence black preachers had on the lives of their congregations. He also experienced strict segregation and the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan thanks to the release of D.W.Griffith’s film Birth of A Nation.

Garvey returned to Harlem with a firmer vision of the need for black separatism, black pride and black economic empowerment. He proclaimed that blacks from the American South were fortunate because the southern system of segregation demonstrated the need and importance of racial power. Rather than acquiesce to the white power structure, black people would aquire their own power through personal and economic self sufficiency. Ultimately Garvey would call upon his followers to establish a new homeland in Africa.

During the years 1918-1919 Marcus Garvey became the most renowned militant propagandist for the Negro. Initially skeptical of black participation in the Great War, Garvey celebrated the accomplishments of the men of the Harlem Hellfighters, the black regiment that served heroically in France. After the war he embraced the new militancy among blacks who were subjected to all the injustices that they had supposedly been fighting against in Europe. Eleven black veterans were lynched in the south. Garvey began publishing the Negro World Newspaper with an eye towards distributing it to black people throughout the Atlantic World. When the West Indian Regiment staged a mutiny in Italy after being ordered to clean the white troops’ latrines, the British government blamed Garvey’s newspaper for inciting the black soldiers.

The fact that a newspaper published in Harlem, New York City could impact a British regiment in Italy speaks to the power of Paul Gilroy’s Black Atlantic Counterculture of Modernity Thesis. Just as social media and the internet connect like minded groups throughout the world, so did Marcus Garvey’s U.N.I.A. newspapers connect black people throughout the Atlantic World. Gilroy goes so far as to postulate that the culture of the African Diaspora created by the transatlantic slave trade was distinct from any one nation, more like a ship sailing between Africa, Europe, The Caribbean and The Americas.

Garvey’s militancy attracted many adherents during the chaotic Red Summer of 1919. Race Riots occurred throughout the United States, the Caribbean and The British Isles. For the first time blacks fought back. Garvey’s call for race empowerment appealed to many blacks. The U.N.I.A. was unique because it had no qualification for membership. Garvey’s organization was not restricted to members of a certain class.

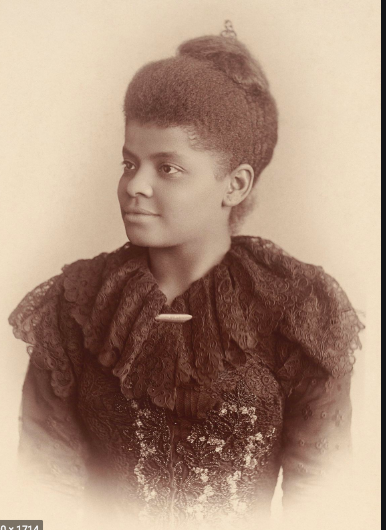

In Harlem, Garvey’s U.N.I.A. founded a laundry, a cafeteria and The Phyllis Wheatley Hotel. Garvey invited Ida B.Wells to visit the U.N.I.A. in Manhattan. He showed her the hotel, cafeteria and laundromat, complaining that his employees were not always hard working or qualified enough for their work. For this reason Wells was astounded when Garvey announced his plan for an all Negro Black Star Shipping Line. Wells warned Garvey that the plan may be too bold for the moment. Garvey responded by having her escorted from the premises and put on the first train back to Chicago.

As it turned out Wells was correct in her assertion that The Black Star Line was too much, too soon for Garvey to take on. However, it was the media attention paid to the idea of an All Negro Shipping Line and the subsequent sales of Black Star Line Stocks that propelled Garvey and his U.N.I.A. to new heights of fame and attention. Unfortunately, Garvey became a demagogue, a man able to stir up his followers and raise a great deal of money while doing so, but not a man able to oversee a successful shipping line.

Between 1919-1924 Garvey became recognized as the most influential leader of Negroes. He made enemies of white leaders who feared his influence over black people and black leaders for the same reason. His differences with the N.A.A.C.P intensified. He and his organization became more racist, seeking to advocate for stricter separation from whites and to undermine the idea that people of mixed race were true Negroes. This colorization issue peaked when Garvey visited the offices of the Ku Klux Klan while on a fundraising tour of the southern states in 1923. This is what a demagogue can do. Engage with the enemies of those he claims to represent as a show of his overall brilliance. Nothing ever comes of these engagements, just media attention that brings criticism from enemies and support and excuses from followers. As Garvey faced mail fraud charges and the prospect of imprisonment, violence ensued. Garveyites loyal to Marcus Garvey assassinated the Reverend James Eason, the leading African-American Garveyite in Louisiana. Although the assassins came from Garvey’s Harlem Headquarters it was claimed that the men had acted on their own initiative. Like demagogues before and after him, Garvey blamed his critics and members of other oppressed groups when he was sentenced to prison. For the first time he issued anti-Semitic statements because the judge who presided over his mail fraud trial was Jewish. Anti-Semitism was also used to explain away the fact that The U.N.I.A. lost its bid to purchase land and establish a place for Garveyites in Liberia, Africa.

In 1925 Marcus Garvey began serving a prison term at the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia. His job at the penitentiary was cleaning bathrooms. In this way, White America made it clear its expectation that black people were meant for only the most manual service roles. Although Marcus Garvey had behaved in a fraudulent manner, the government’s evidence was an empty envelope, presumably used to sell stock in a ship that The Black Star Line did not have possession of. Author Colin Grant points out that Warren Harding’s Secretary of State Albert Bacon Fall received a much lighter sentence for The Teapot Dome Scandal, which was at the time the greatest financial fraud ever committed in The United States.

Garvey was deported to Jamaica in 1927. Garvey’s U.N.I.A. fell apart without its leader present. By the 1930’s Garvey was struggling financially. He’d left Jamaica for London, England where he resorted to giving soapbox speeches in Hyde Park. Meanwhile, his former ship captain Joshua Cockburn became a wealthy real estate operator in Manhattan. Garvey blamed the complete failure of The Black Star Shipping Line and his U.N.I.A. on his first Ship Captain.

Although Garvey and his U.N.I.A. lost influence, it is notable that the parents and grandparents of more recent civil rights leaders were Garveyites. In her autobiography Rosa Parks notes that her grandfather was a follower of Marcus Garvey. Malcolm X’s father was a Garveyite. Ruth Batson, a Boston civil rights leader who started the METCO Program for Boston area schools, recalled that her mother was a Black Star Nurse. Dr.Martin Luther King Jr. states on page 33 of his book Why We Can’t Wait:

After the First World War, Marcus Garvey made an appeal to the race that had the virtue of rejecting concepts of inferiority… His movement attained mass dimensions and released a powerful emotional response in the mind of the Negro. There was reason to be proud of their heritage as well as of their bitterly won achievements in America.

In popular culture, Marcus Garvey is venerated by the Caribbean Religion of Rastafarianism. Garvey and Halie Selasie make strange bedfellows, seeing as how Garvey celebrated Selasie at first, then criticized him. Selassie completely ignored Garvey and his contingent when he came to England after being exiled from Ethiopia. Sadly Selasie later completely ignored his starving people which led to a Communist Revolution in his country. Although he had been a powerful demagogue for a brief time during the early 1920s, Garvey did not stop advocating for black people after all power was taken from him. Marcus Garvey’s greatest contribution to Western Civilization is the idea that people of African Descent have a history and have talents that have been forsaken and taken for granted and that this condition must be remedied. Although he himself became mostly forgotten in The United States his influence can be seen in Africa where The Nation of Ghana adopted the colors of the Garveyite Flag into their own National Flag.

At present, Marcus Garvey’s impact is different based on where in the Atlantic World one chooses to look. In the United States, he is venerated for his focus on black people’s unique place in American History, what Dr.King called their proud heritage, and bitterly won achievements. So Garveyism means Black Pride and knowledge of Black History. In the Caribbean, he is a native son, especially in Jamaica where his body has been interred at Hero’s Park in Kingston since 1963. In West Africa, Garvey is remembered as the voice of anti-colonialism. But during his own time at the height of his influence, he was a demagogue who met with the Ku Klux Klan in America, struggled to have any direct influence on political events in Jamaica and the Caribbean, and never set foot in Africa while running an organization whose meetings modeled the pomp and circumstance of The British Parliament. Marcus Garvey started with virtually nothing as the son of a former slave in Jamaica, became the leader of an Improvement Association and Shipping Line in The United States was jailed and deported to Jamaica, and died penniless in London, England. Garvey predicted his experience when writing about how he became a race leader:

I read Up from Slavery…and then my doom-if I may call it- of being a race leader dawned upon me. I asked “Where is the black man’s government?… Where is his President, his country, and ..his men of big affairs?” I could not find them, and then I declared “I will help to make them.”